This article is based on a recent letter to clients from Alan Elizondo, partner at the Costa Rican law firm Venture Legal

If you haven’t heard by now, last week the Supreme Court of Costa Rica handed down a surprise Indigenous land decision that has the potential to negatively affect property owners in the south Caribbean. Essentially, the boundaries of the Kekoldi Indigenous Reserve were modified drastically, and now include a large portion of land that previously wasn’t within this indigenous reserve. Unfortunately, the effects of the ruling are not clear yet; there is a lot to analyze and a lot of questions that still remain unanswered.

History of the Dispute

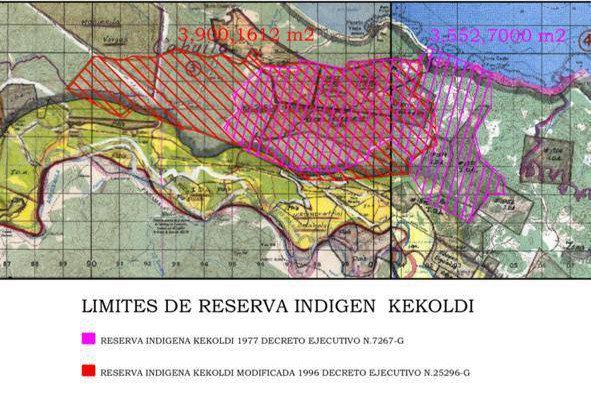

The original Kekoldi indigenous reserve was created in 1977 through executive order N. 7267-G. The area is marked in the following map with the pink and pink/red overlay:

However, the government determined that the coastal area was not really used by the Kekoldi, who seemed to prefer the mountainous portion, and therefore in 1996 the government issued executive order N.25296-G, in which they “exchanged” the coastal area on the east of the map for additional mountainous land on the west, marked in red in the above illustration.

Then, in 2010, the Kekoldi Association of Development filed a lawsuit against CONAI (National Commission of Indigenous Affairs), the State, and other entities in an attempt to restore the borders granted by the original executive order of 1977.

The lower court that heard the case ruled against the Kokoldi and in favor of CONAI and the State. Then, in a subsequent appeal by the Kekoldi, the Superior Court sustained the lower court’s ruling against them. The Kekoldi then filed a second appeal, and the case was escalated to the Supreme Court.

Supreme Court Ruling

Ten years later, the Supreme Court has overturned the ruling of the lower courts and ordered that the government honour its 1977 executive order that granted the rights of the coastal land to the Kekoldi.

The stated reason for the Supreme Court’s decision was that the executive order from 1996 didn’t follow the due process established in the 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention. This convention established that in order to modify the areas of an indigenous reserve, a formal consultation process had to be conducted and approved by the Kekoldi. The court concluded that the consensus was very informal and violated the rights of the Kekoldi.

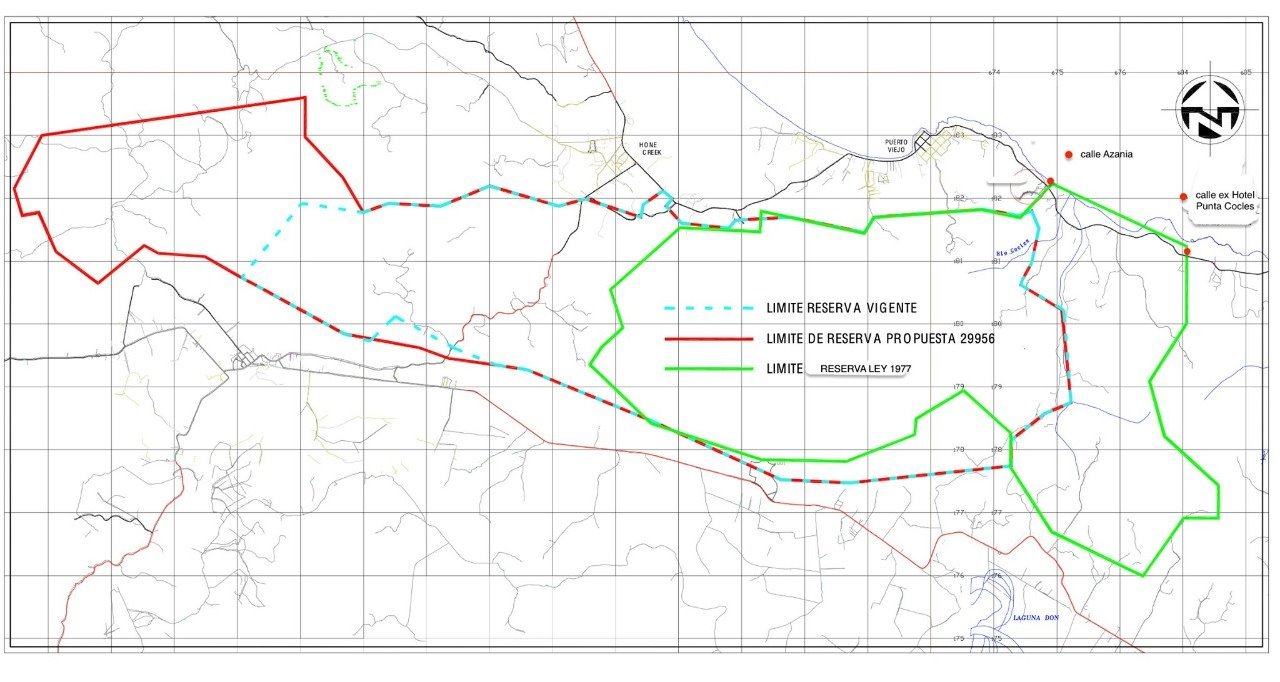

The court therefore effectively voided the executive order of 1996 and restored the 1977 executive order, re-absorbing an area that includes many existing privately-held properties (green-outlined area on the map below). That being said, the exact boundaries are not even clear, since the 1977 executive order was written without the benefit of the modern tools we have today to establish precise boundaries.

As a result of the court’s decision, many want to know what CONAI’s position on these developments will be. So far, they haven’t provided a clear answer except that the ruling is under study and they will file a “clarification and addition” petition in order to fully understand some points that they believe are blurry.

What does it all mean?

It is important to mention that this ruling is not going to be immediately enforced against members of the community living in the affected area. As all of the current property owners bought their properties in good faith, the government will have to pay compensation for their losses, and for that there is both an administrative and a judicial process to determine the fair value of the property.

What still remains a question is how the government would obtain the necessary funds to expropriate all these owners when the national budget is barely able to cover the existing basics.

That being said, the government still has the option to make things right, and issue a law in full compliance with the 1989 Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention in order to reset the boundaries of the Kekoldi Reserve. However, to issue this law the Kekoldi will need to approve and consent to the modifications, which would most likely come at a price. This would still most likely be less expensive than compensating all the owners that currently inhabit the land.

What next?

Prior to 1996 it became clear that the coastal portion of the affected area was not destined for indigenous use, and never had been. That was actually the original motivation to modify the boundaries in 1996. However an “error” in the due process of the executive order of ’96 has caused all this chaos in the community.

The approximate limits of the Kekoldi Indigenous Reserve from 1977 are between la calle Azania (La Costa de Papito hotel) to the former Hotel Punta Cocles, so if your property is located within those limits we strongly suggest you request a formal certification from CONAI to determine whether or not your property is affected by this indigenous reserve. If affected, we will need to sit tight and wait to see where the winds blow in order to obtain the best outcome for you.

Alan Elizondo is a founding partner of the law firm Venture Legal and holds not only an extensive practice in civil, commercial, notarial and real estate law, but also a Master’s in Business Administration from the prestigious Institute of Stock Market Studies, in Madrid, Spain. It allows to include a more business-oriented vision within its services. He has worked in several of the most experienced law firms in the country. Co-author of the thesis entitled “The Financial and Securities Intermediation in the Costa Rican Legal System”, approved with distinction as well as recommendation for publication at the University of Costa Rica.