(Lee este artículo en español)

Bigger means better, and more tourists mean more money, right? Local economies thrive, the agriculture sector flourishes, and countries with few natural resources or development finally play ball with the big boys.

Or, is the concept of sustainable mass tourism just a ploy to get multinational chains and all-inclusive resorts into local neighborhoods? A capitalistic wolf in sheep’s clothing, so to speak.

Ask business owners operating in the travel industry if large scale resorts and mass tourism can be good for the environment and local communities, and you’ll likely get answers that are as polarized as U.S. national politics.

Looking to the future

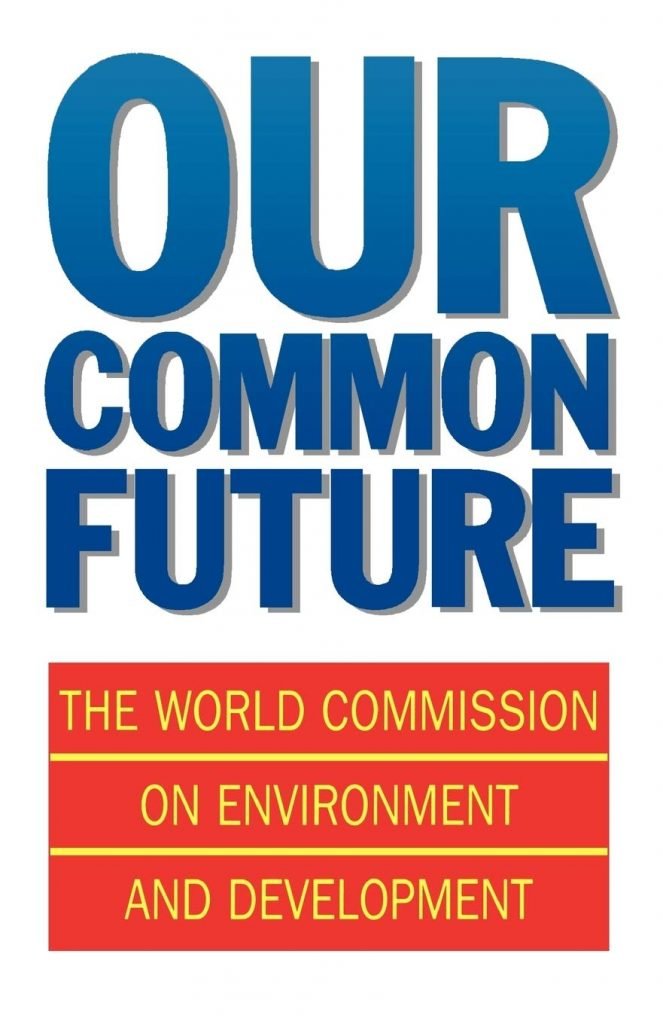

Our Common Future (PDF), also known as the Brundtland Report, was presented to the UN General Assembly in 1987. The nearly 400-page document established a foundation for what would later become the unprecedented UN Sustainable Development Goals, a call to action for world countries to commit to tackling environmental degradation and human inequality, among other critical issues.

According to the report, “Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

When applying the concept of sustainable development to tourism, the wellbeing of each social and ecological component of the supply chain is considered. It is an industry-wide commitment to having positive (or minimal) impact on the environment and local communities, providing employment for residents, purchasing locally sourced food and materials, and generating awareness among visitors.

“Today, the business volume of tourism equals or even surpasses that of oil exports, food products or automobiles. Tourism has become one of the major players in international commerce, and represents at the same time one of the main income sources for many developing countries,” according to a UN World Tourism Organization report.

When tourism hurts

In a recent publication by CNN travel, Justin Francis, CEO of Responsible Travel, argues that large-scale resorts have the potential to solve the dilemma that over-tourism presents in several world destinations.

“Residents are saying that having too many tourists in the places they live is degrading the quality of their lives,” he says. “The places they want to rent, or buy are being taken out of the market, the price of living is going up, and the streets are becoming overcrowded.” This is likely exacerbated by the rise of short-term rentals.

Where does Costa Rica fit in?

Even during Costa Rica’s high season, visitors can still find stretches of deserted beaches, quiet trails through pristine rainforest, and wildlife coexisting with human populations in small local communities.

Is it possible that one day, tourists will bump and shove each other out of the way to glimpse a three-toed sloth chewing leaves (the Central American equivalent to the Mona Lisa)?

And will short-term rentals like Airbnb eventually push local residents out of their homes and neighborhoods? The very communities visitors came to experience?

With the country’s growing popularity as a world-class vacation destination packed with biodiversity and adventure tourism, it’s certainly a possibility. The task now is to determine if large-scale resorts and pre-packaged vacations are the answer, or even desirable, for the nation’s future.

“All-inclusive models don’t have much impact on local residents because there are no local residents. It was previously thought that keeping tourists in a compound was a bad thing, but it eliminates potential issues in destinations where locals are trying to live alongside large numbers of tourists,” said Francis.

Many supporters of sustainable tourism staunchly resist the idea of mass tourism or large-scale resorts moving into their communities. Yet, before taking sides, it’s important to define what the small-scale model really looks like and what degree of impact it will have when compared to the alternative.

“How many boutique eco-lodges and mom-and-pop hotels have to be carved into the rainforest to equal the same amount of local economic activity as one Marriott?” asks Colin Brownlee, owner of Banana Azul, a 25-room boutique hotel on Costa Rica’s Caribbean coast.

“Huge numbers of small hotels crowded into a beachfront community is not sustainable. Smaller doesn’t automatically mean better when it comes to benefiting the community and environment, nor does it mean less impact. It’s time for us to have the conversations that few small-business owners or faux environmentalists want to have,” he adds.

“Besides”, Brownlee continued, “when it comes to serving the community, most large-scale outfits guarantee employee training, benefits, and compliance with local labor laws. From what I’ve seen, that’s not always the case for smaller venues. But ask a small-scale eco-hotel in Costa Rica if they’re doing their part for the community, and I’m sure you’ll get an unqualified ‘Yes’.”

Eco-boutique vs. the Marriott vs. Mom-and-Pop

When comparing options for which sustainable tourism model best suits the current and future needs of local communities, the environment, and the national economy, there are several factors to be considered. Pros and cons for each scenario spark heated debate among the advocates of either side.

One inarguable fact, however, is that development IS coming to Costa Rica. In fact, it’s already here. Now is the time for the opposing sides to stop recycling the same old unproductive narratives and begin collaboratively working toward the assurance that sustainability and the needs of local communities are taken into account as the economy grows – and not just that anti-development activists and pro-development multinationals set the agenda.

According to the CNN report, the key to living with a steadily growing tourism market is to get large-scale resorts to change their behaviour. The first step is to hire and train locally, as well as source local products, tour providers, transport, and restaurants. Another key is building sustainably with ecologically smart initiatives and government incentives. It also entails changing the public perception that all-inclusive is synonymous with budget travel.

What’s more, big resorts like the Marriott or the Hilton are already highly regulated and exposed to public and government scrutiny. It is far less likely that such a hotel chain can fly under the radar for non-compliance with local environmental or labor laws, unlike smaller venues, like the mom-and-pop shops.

And then there’s NIMBYism

NIMBY, an acronym for the phrase “not in my back yard,” characterizes the opposition of residents to a proposed development in their local area. Often, and particularly in Costa Rica, the majority of “NIMBYs” are often foreigners (legal and/or illegal residents, not full citizens) taking up the just cause.

It should be noted, however, that this political activism isn’t legal. According to immigration lawyer Fernando Solís, the terms of temporary and permanent residency in Costa Rica prohibit non-citizen foreigners from participating in domestic political activities:

In fact, a significant percentage of Costa Rica’s “local” populations are first- and second-generation foreigners who immigrated permanently to the country years, if not decades, ago. According to 2016 statistics from the Department of Immigration, Costa Rica is home to 488,935 foreigners with resident status, of which 379,901 held permanent status.

Immigrants who originated from the U.S., Canada, and Europe, typically those most likely to be involved in political activism by foreigners, shouldn’t overestimate their own significance, however. Those immigration statistics reveal that legal immigrants from those countries make up only 10% of immigrants foreigners – just 1% of the total Costa Rican population. The biggest bloc of immigrants, by far? Those from Nicaragua – they number over 329,000.

Many NIMBYs argue that development and commercialization are bad for the communities (that they themselves recently moved into). They argue that change should be kept to a minimum, and the wild places should remain frozen in time—even if they’re plagued with poverty and scarce opportunity for local residents.

There’s only so much room for growth, however, and if Costa Rica really wants to keep things wild, then building a harmonious and clearly defined relationship with development is a must. And contrary to popular perception and narrative, not all entrepreneurs are out to see the country transformed into a high-rise jackpot.

It’s inaccurate to assume that the foreign element is out to exploit; on the contrary, most permanent residents and naturalized citizens are devout defenders of the national well-being and the integrity of the communities they call home.

When asked about the proposed zoning for large-scale resorts around the Caribbean capital of Limon, Christer Eriksson owner of Koki Beach Restaurant in Puerto Viejo replied, “Limón is a homogeneously poor province – 27% of its households live in poverty and with low schooling rates where only a quarter complete high school. They are effectively shut out of the employment market, condemned to survive in the informal job market and living on or under the poverty line. The tourism sector generates an opportunity for the population to overcome its stagnation on the Human Development Index. Tourism in Costa Rica provides jobs, training, healthcare, education, security, and environmental consciousness for thousands of families. And tourism income is democratic because it helps all segments of the community, directly or indirectly, from the artisans selling their crafts, to owners of a Paty stand or Soda, and those who work in hotels or transport. Sustainability means we not only protect our ecosystems and natural resources but also the well-being of people and their spaces, in addition to offering healthy equitable economic development opportunities. This can be done.”

Regardless of their position either for or against development, when speaking with local residents and business owners in Costa Rica’s South Caribbean or other coastal towns, one prevalent theme becomes clear: what the areas desperately need is straightforward and effective regulation.

Regulations – neutral territory

A well-developed and -implemented regulatory plan is the best solution for controlling uninhibited growth in local communities by outside parties. In Talamanca Canton, the national and provincial ministries, university academics, rural and indigenous community leaders, business owners, residents, and environmental councils have invested considerable time and effort into defining what can and cannot be done within their communities and the surrounding environment.

“There has to be full and total public participation in upholding the regulatory program. If the associated laws were being enforced like they’re supposed to be, then there wouldn’t be this wanton development,” says (foreign resident of Costa Rica) Carol Ingrid Meeds of Earth Stewards of the Caribbean, a non-profit initiative working for the protection and preservation of the Caribbean coastal maritime zone.

In fact, it is the citizen-elected municipal governments that effectively develop and implement zoning and regulation laws as well as determine when they will come into effect. It therefore seems somewhat disingenuous for organizations like Earth Stewards to assert that the laws are not being enforced “like they’re supposed to be.” Furthermore, it often seems that their focus of attack is misplaced when they’d rather go after beneficial tourism than, say, the enormous multinational banana plantations whose run-off and by-product has likely done far more damage to the Costa Rica’s maritime zones and coral reefs than all of the country’s tourism businesses combined.

However, according to Alvaro Alcala at the Institute for Municipal Development (IFAM), a publicly owned operation that provides training and technical assistance to municipal authorities and officials, as well as financing to support the development of municipal plans, “The reality is that only 40 percent of Costa Rica’s 81 cantons have up-to-date zoning plans due to legislative setbacks, failure to comply with certain requirements, and other reasons.”

The future of Costa Rica’s South Caribbean

When, exactly, the regulatory plan for the South Caribbean will come into effect is unclear.

What is clear, however, is that the lack of defined regulatory zoning is effectively fracturing the community into a hotbed of resentment, suspicion, and finger-pointing.

Foreign business owners are being accused of favoring profits over the community and the environment; politicians and local leaders are being accused of corruption and fraud, and environmentalists are being accused of halting any and all progress, regardless of what it’s good, or bad, for.

“What’s really bizarre is that we’re all here for the same reasons,” said Eriksson about the current state of affairs. “Because we love the people and the environment, and we don’t want this to be lost.”

“It’s important to keep in mind that Costa Rica’s image is built on environmental consciousness and breathtaking nature – this is literally the country’s brand. That’s why it’s imperative that we protect that. Talamanca has more than three times the national average designated as protected areas encompassing the vast majority of its territory. This makes it even more important to implement a zoning plan (Plan Regulador) to achieve sustainable development for coastal areas as mandated by law,” he adds.

The 358-page 2014-2024 Human Development Plan for Talamanca Canton specifically targets the challenges facing a full gamut of sectors, including education, social, environmental, infrastructure development, health, security, and national and foreign investment, among others. The plan identifies existing target (problem) areas and their causes, and formulates a series of solutions, objectives, and activities/projects, and anticipated results.

Real sustainability

With effective zoning plans in place, local governments can decide how many large-scale resorts or boutique mom-and-pops are permitted to build and where. Without the implementation of such regulations, however, corruption and mayhem are likely to continue, and turn Costa Rica’s pristine coastal areas into tourist traps reminiscent of the Maya Riviera.